James Cave

b.1979, Cambridge, England

James Cave is a composer and singer with a particular interest in collaborative practice. During his residency at the Mahler & LeWitt Studios he will be working on a new composition titled Returns, an opera in one act which is based on the play by Joshua Casteel.

Casteel (1979-2012) was an Iraq veteran turned peace campaigner and playwright. At aged 27 he died of multiple cancers contracted as part of the cleansing procedures involving contaminated material facing the army in Iraq. His work attracted widespread attention, including a performance at the Royal Court, London for Human Rights Watch. It was also seen at the Abbey Theatre, Dublin and Princeton University.

Returns, directed by the Mahler & LeWitt Studios Artistic Advisor David Gothard, is based on Casteel’s own experience of post-traumatic stress and revolves around the struggle of James (baritone) to organise his memories into a coherent narrative. The other characters in the opera each represent aspects of James’ fragmented consciousness. In a 20-minute extract from Returns, premiered at Rough for Opera 13 (York, UK), Cave combined Indian tala rhythms with a taut operatic language to dramatise the narrative.

Cave was recently the recipient of a Terry Holmes Award and a Sir Jack Lyons Celebration Award for Composition. In 2015 he was Composer-in-Residence at the Banff Centre (Banff, Canada) and participated in the inaugural World Music Residency in Eastern Traditions. He is a permanent member of York Minster Choir and a member of the Gavin Bryars Ensemble with whom he has performed internationally. Most recently he performed Beckett’s Songbook with the ensemble at the Centre Culturel Irlandais, Paris, as part of Sean Doran and Adrian Dunbar’s ‘Happy Days Festival’.

Recent compositions include Latrabjarg, commissioned by the York Spring Festival of New Music, in which Cave worked with an electric cellist and soundscape artist to weave together saga texts, bird-calls and folksong to evoke the disintegration of Iceland’s ecosystem. Fothcoming works include Eonsounds, a collaborative project exploring the links between music and geology, with geologist Dr Tim Ivanic and spatial sound-researcher Dr Jude Brereton.

During his residency, at the request of one of our writers in residence Rye Dag Holmboe, who himself has research interests in seriality in the visual arts and literature, James delivered a fascinating lecture, for invited guests, exploring the history of seriality in music. In a second event he presented his opera as a work in progress to Teatro Lirico Sperimentale, the Spoleto based opera prize and commissioning body.

The devastating earthquake which shook central Italy in August 2016, a week into the residency session, had its epicentre 50kms away from Spoleto in the Valnerina. We felt it keenly in Spoleto and it upset the rhythm of work at the studios – a negligible price, comparatively. James, who has an ongoing project in collaboration with geologist Dr Tim Ivanic, explored his experience of the quake and its aftershocks in a sensitive and evocative blog post for the University of York Music Department titled ‘La Terra Trema’:

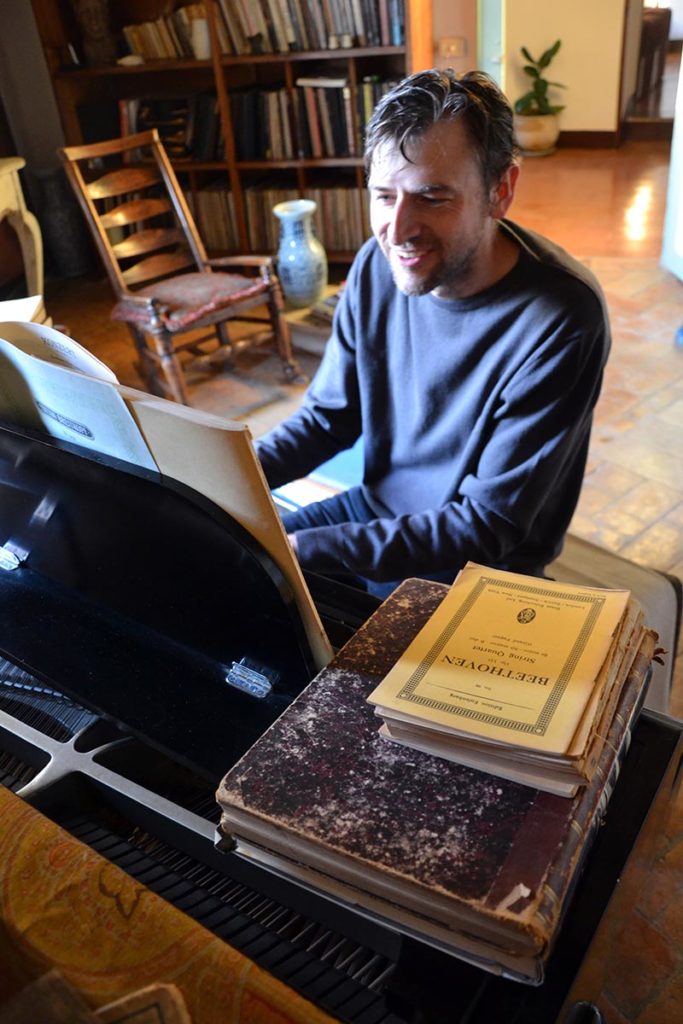

On a secluded backstreet in the ancient Italian town of Spoleto, there is a house full of statues. Open its heavy oak front door, and you are greeted immediately by an imposing stone figure guarding the central courtyard. Entering the main body of the house, you meet a reclining figure; climbing the stairs, a vast mask stares down upon you with unblinking eyes. On the first floor, in a stately music room flooded with light, and lined with scores, a series of busts of musical luminaries – Mahler, Schoenberg, Klemperer – look down unwaveringly across the curved form of a Steinway grand.

Gustav Mahler’s sculptor-daughter, Anna, bought this house in the late 1960s, and swiftly populated it with examples of her work, making it her home and studio until her death in 1988. To this day, the house remains a family home, but it is also the venue for an innovative artistic programme, the Mahler & LeWitt studios.

Spoleto has a lengthy and varied artistic and cultural history stretching from Roman times to the present day. Its cathedral boasts frescoes by the great Renaissance artist Fillipo Lippi, and the town is an architectural masterpiece in its own right. In 1958, the Italian-American composer Giancarlo Menotti founded a major arts festival in Spoleto, the Festival dei Due Mondi. At the time, people suggested that Menotti was a crazy fool – ‘il matto’; though splendid, the town had few hotels for festival-goers, and was over an hour away from Rome by train. But over the years, audiences flocked to Spoleto, to see performances by Pavarotti and Nureyev, amongst others, and to attend exhibitions of work by artists such as Alexander Calder. Menotti, ’Il matto’, was vindicated and hailed as a hero: there is a small family-run restaurant just off the main square in the historic centre, Osteria del Matto, that commemorates this triumph through its choice of name.

Spoleto’s vibrant artistic life began to attract internationally acclaimed artists, in addition to Anna Mahler; the eminent American artist Sol LeWitt began to work in Spoleto from the 1970s onwards, and finally relocated to the city from New York around 1980. LeWitt bought a house perched on a hillside overlooking the town, perched above a vast chasm spanned by a Roman aqueduct, the Ponte delle Torri, and later a studio in the town’s historic centre. Following the lead of fresco painters centuries earlier, LeWitt began to embellish the walls of villas owned by friends with his own striking geometric forms, and producing designs for local ceramicists.

In an intriguing twist of fate, it turns out that Sol LeWitt and Anna Mahler were in one way, near neighbours; LeWitt’s studio space directly adjoins Mahler’s spacious casa. In 2010, their shared artistic legacy became the basis for a new venture, a residency programme initiated by the Anna Mahler Association. In 2015 it became known as the Mahler & LeWitt Studios. During the summer months, Casa Mahler and LeWitt’s adjacent studio play host to an international community of artists, writers, researchers and curators as part of an extensive residency and projects programme. In 2016, I was fortunate to be selected as the first-ever Composer-in-Residence, sponsored by the Anna Mahler Association, in order to complete a first draft of my opera, ‘Returns’: I have been in residence at Casa Mahler, working in the music-room, since August 15th.

The casa was a place of tranquil retreat and a productive workspace until two nights ago. At 3:36am a massive earthquake, measuring 6.2 on the Richter scale, hit the picturesque mountain-towns of Amatrice and Accumoli near the Lazio-Abruzzo border. Reverberations buffeted the walls of Casa Mahler, some 40 km away from the epicentre, causing walls, floors and furniture to shake violently. The first tremors roused the house’s inhabitants from sleep; the first aftershock, not much less violent than the initial quake, made us gather in pyjamas on the stairs of the house in shock and surprise. Swiftly, we realised that the violent shaking that had woken us up was in fact the edge of something much larger. The initial indications from Amatrice, which we read minutes after the earthquake were chilling: ‘half the town has disappeared’ said the town’s mayor, ‘and all the lights have gone out.’ We hoped that this was exaggeration; sadly this has not proved to be the case. At the time of writing the death toll from the earthquake is around 270, with hundreds of others injured in hospital. The images from the stricken towns are heartbreaking.

Italians use the word terremoto for earthquake, but they also use the word sisma, which if I am correct contains the idea of a wave or vibration. And that is what earthquakes, in all their monstrous unpredictability and devastating impact, are; giant reverberating waveforms. If I grasp the geology correctly, the discharge of wave-energy within a shallow tranche of earth, as has just happened here, will cause massive repercussions – and violent shaking at the epicentre. Further away the discharge of energy – in the case of this earthquake, roughly equivalent to the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima – is felt, but not as keenly.

And, as we musicians may understand from studying the science of sound waves, the expansion of energy in earthquakes is exponential not linear: each degree increase on the Richter scale is an increase of ten times in the power of the earthquake with a 6 being 100 times more powerful than a 4. The other quality of earthquakes that is difficult to grasp is that each major incident precipitates a complex echo-pattern of aftershocks. These aftershocks are typically less intense that the main event, but vary in their exact force and distribution according to the fractal arrangement of the fault-lines that cause them. Peculiarly, earthquakes are so rigorously monitored that I can tell you, by using the website http://www.emsc-csem.org, that there have been three aftershocks since I started writing this article, one (at 3.8 on the Richter scale) strong enough to cause slight reverberation at Casa Mahler. And they continue.

Peculiarly, at the same time as finishing the score for ‘Returns’, I’ve been working on a new collaboration with geologist Dr Tim Ivanic, Eonsounds. (www.eonsounds.org). The aim of this project is to use sound and music as a means of enabling an audience better to understand the ways in which the earth itself acts like an organism, but on a vast scale and with significant events often occurring huge number of years apart. Dr Ivanic and I are interested in finding ways that the earth’s lifespan, all 4.4 billion years of it, can be better grasped through the innovative transformation of data into sound, and, in order to do this, we’ve been working with a fantastic team of creative researchers, including data-sonification expert Dr Jude Brereton and Carnatic classical singer, Supriya Nagarajan. Experiencing an earthquake is, of course,terrifying; but working with my colleagues on this project has enabled me at least better to understand the nature of this experience.

The reverberations of an earthquake are of course, psychological as well as physical. Working on ‘Returns’ which dramatises the effects of combat stress on Iraq veterans, I’ve learned that traumatic experiences can lie dormant in the memory for years, only to awaken suddenly in a rush of emotions, images and sensations than can feel as intense as the original event itself. This morning I woke suddenly in a panic: looking at my phone, I saw that the time was close to 3:36, the time at which the earthquake struck two nights earlier. This is a mild form of traumatic repetition, but traumatised communities can experience the after-effects – the after-shocks – of traumatic incidents for generations. These communities must be – physically – rebuilt, but they must also be healed.

In 1981, the artist Alberto Burri was invited to visit the town of Gibellina in Sicily, which had been decimated by an earthquake thirteen years earlier. Having visited the new city, Burri then asked to be taken to the ruins of its earthquake-stricken predecessor. Deeply moved by this experience, Burri determined to build a memorial to the town. He created the vast Grande Cretto of Gibellina, which entirely covers the ruins of the town, being 300 by 400 metres in size. The cracked cement surface of the work, evokes both the landscape in which it is situated, and the vast geological processes which tore the town apart. Of this work the architect Alberto Zanmatti writes: ‘Old Gibellina, will remain for those who lived there a place of continual pilgrimage, in memory of their dead and their past life. The ‘cretto’ or crack [of Burri’s work] almost a figuration of the earth which shook, becomes a pathway where old roads meet up, a labyrinth of memory which proposes a new life…[it enables] the people of Gibellina…to rediscover themselves by remembering how things were and accepting how things are.’